Discussion Paper:

What is the difference between Facilitation and Team Coaching?

Elle Taurins

1 March 2018

SYNOPSIS: As a Facilitator and Coach, I often pondered over the distinction of ‘group facilitation’ and ‘group coaching’ concepts. When facilitating, I employed many coaching approaches for successful learning outcomes, including ‘Socratic questioning’. As a Coach, I felt I was facilitating processes of deep learning and self-reflection. This Discussion Paper aims to define and analyse the distinction between the concepts. Although authoritative sources are cited, the paper does not aspire to make it an academic piece. The purpose of writing was to gain an insight into how these two functions of coaching and facilitation impact on team effectiveness in organisations.

The paper provides a brief overview of the evolution and different perspectives of Facilitator’s role since the 1960’s. The core competencies of Facilitators and Coaches are compared, as defined by respective international professional organisations.

The early 90’s featured an emerging discourse of a ‘team’ concept as opposed to a ‘group’. Some points in evolution of the ‘team’ definition are presented prior to moving to the overview of team effectiveness models and team coaching definitions. A few systemic team coaching models are presented and compared with a focus on Hawkins’ (2014) and Lencioni (2012) models.

My exploration of this topic suggests that clarity between the Coach’s and Facilitator’s roles would yield more effectiveness in transforming organisations. Team Coaches, however, would need to integrate their facilitation skills into coaching processes to enable core organisational learning.

Writing this paper was a genuine learning experience for me, and I would like to invite and encourage a collegiate discussion of practitioners in this developing field of team coaching.

Evolution of concepts

The concept of Facilitation can be dated back to ancient times of over 3,000 years ago when our ancestors used to sit in discussion circles to make important decisions for their community. In the 20th century, the term ‘facilitation’ was used in many fields, such as education, research, mediation, and organisational processes. The word is derived from the Latin “facilis” (easy to do). Meeting facilitation started to appear as a formal process in the 1960s and was closely linked to P. Senge’s concept of the Learning Organisation (LO) (1).

Benefits of the facilitation process include higher meeting productivity, empowerment and personal commitment to the organisation’s plans (Kaner, 1996). In the formal process of facilitation the focus was on building awareness and enabling learning. In the late 90s, Facilitators became content neutral and their role expanded into advocates for inclusive process that would improve productivity and establish a safe psychological space (Doyle cited in Kaner, 1996). It is worth noting that the organisational development literature of the time did not distinguish the concepts of a ‘group’ and a ‘team’.

The evolution of the concept of facilitation yielded multiple perspectives on a facilitator’s roles. Bimrose et al. (2014) suggest that humans, tools (i.e. technology) and environment (i.e. workplace environment) may take on role of facilitators. The authors (ibid.) propose that individuals as facilitators perform and frequently change roles as coaches, moderators and facilitators in group learning processes.

This suggests that the above mentioned facilitation discussion is not concerned with the distinction between ‘groups’ and ‘teams’. Definitions of Facilitation provided by the International Association of Facilitators, IAF (2015) propose that Facilitator controls the process, does not provide content, and works with the client or group to define a session purpose and output. Their role is “strictly one helping the group manage the information they already possess, or can assess, to achieve a necessary result in a timely and collaborative manner” (IAF, 2015). The IAF is more apprehensive about the distinction between the ‘Facilitation’ and ‘Training’ terms. The trainer is defined as an individual who comes to a session with both Process and Contents; Trainers do have contents expertise and decide on the process how the session would be conducted (IAF, 2015).

Facilitation vs Coaching

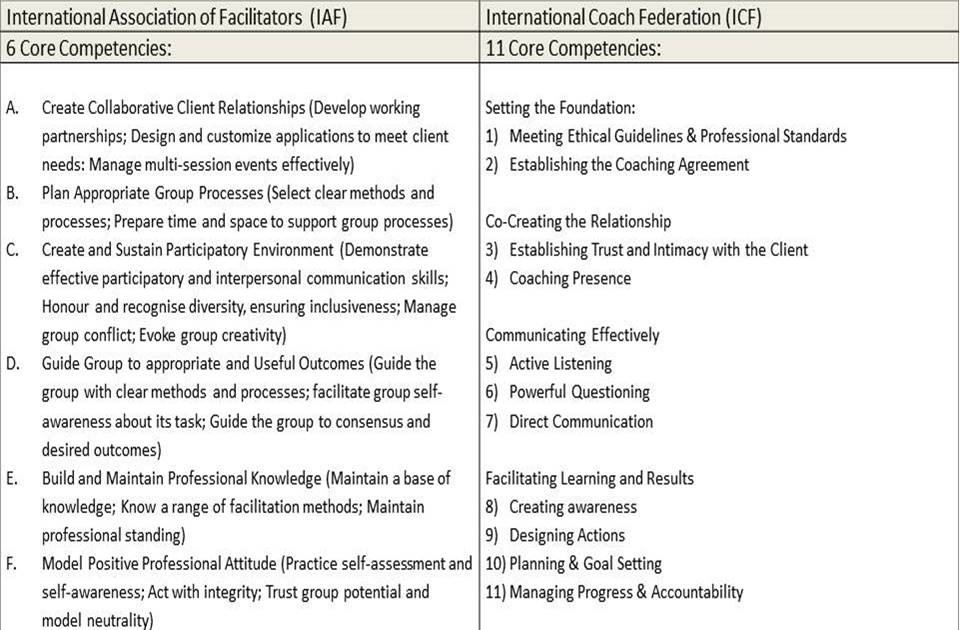

However, the Core Competencies of the IAF have elements in common with the Core Competencies of the ICF. For example, both organisations include aspects of relationships, awareness building, effective communication into their core competencies. For more detailed comparison see the table below:

The overview suggests that Facilitation process is guiding the group, while group coaching relies on the group to drive the process and set direction.

Similarly, Clutterbuck (2007) notes the common confusion between the role of team facilitator and that of coach. The distinction of the roles is summarised in the table (Adapted from Clutterbuck (2017, p. 101-102). In my view, the confusion of the terms is caused by cross-disciplinary professionals. Facilitators use coaching questions as a method of facilitation, while coaches have a responsibility of facilitating learning and results (ICF Core competencies 8-11). Facilitation process aims at guiding the group on how to manage and process the existing information.

Groups vs Teams

In the early 90’s the discussion of organisational effectiveness progressed to evolution of a ‘team’ concept vs a ‘group’. Katzenbach and Smith (1993, reprinted 2005) argues that the word “team” is used so loosely that it gets in the way of applying the discipline that leads to good performance . They propose that “not all groups are teams” (p. 164) and the essence of the team is common commitment. The telling signs of teams are about shared roles, specific team purpose, problem solving and collective work products. While a ‘working group’ discusses, decides and delegates, the team “does real work together” (Katzenbach & Smith, 2005, p. 164).

Katzenbach and Smith’s work energized the discourse on ‘high performance teams’ and ‘real teams’. A plethora of team definitions emerged, for example:

- Richardson (2010, cited in Hawkins, 2014, p. 150) defined the ‘real team’ as “a group of people working together in an organization who are recognized as a team; who are committed to achieving team-level objectives upon which they agree; who have to work closely and interdependently in order to achieve those objectives; … and those who communicate regularly as a team in order to regulate team processes”.

- Cohen and Bailey (1997, cited in Eisele, 2013) differentiated types of teams and identified four key team types: Project teams, Parallel teams, Work teams and Management teams. They argue that the differentiation is necessary for measuring team effectiveness using assessment instruments such as TDS (Team Diagnostic Surveys).

- Hackman (2002, cited in Clutterbuck, 2007) classified teams into manager-led, self-designing, self-managing, and self-governing. The highest level of self-operating teams is self-governing teams such as a corporate Board of Directors.

- Hawkins (2014, p. 151) argues that it is important to distinguish between these types of teams, depending on how the decisions are made (‘decision making team’) or how the new thinking is generated (‘performance team’), or how they engage with stakeholders (‘Leadership team’).

Team Effectiveness and Coaching

- Hawkins (2014) developed an assessment inventory to evaluate team performance, including a Questionnaire used to identify whether the ‘team’ is a work group or a real team. This self-assessment tool would need to be completed by the team members, the team leader or coach. The answers rating high on performance indicators of shared leadership, collective objectives, individual and mutual accountability, specific team purposes, collective work products, active problem solving, and acting as part of the team when they are not together, suggest that the team is ‘real’ (Hawkins, 2014, p. 151). Other tools in Hawkins’ (2014) assessment inventory to measure team performance include Team function analysis (measuring time spent of on team functions in 8 categories) , and Team motivation (matrix measuring the state of energy (p. 155)).

Hackman (2002, cited in Eisele, 2013) developed a Team Effectiveness Model in which he highlighted 3 features of real teams conditions: they are bounded, interdependent and stable. Members have collective responsibility, making them interdependent. The model includes Supportive Organisational Context which proposes that even if the team has clear goals and is well composed, it can still demonstrate poor performance due to a lack of organisational support.

The model includes Expert Coaching and this requires a further discussion of team coaching definitions as well as team coaching models. In contrast to effective teams’ models and assessment inventories, Lencioni (2006) took a reverse view and identified the causes of the five key dysfunctions of teams. He urged leaders to ask important questions to understand the level of dysfunction. The 5 dysfunctions, according to Lencioni (Ibid.), are: 1) Absence of Trust (reluctance to admit mistakes and ask for help), 2) Fear of Conflict (not engaging into a debate about key issues), 3) Lack of Commitment (ambiguity and lack of direction), 4) Avoidance of Accountability (due to lack of direction), and 5) Inattention to results (putting own ego ahead of team goals).

Team Coaching Definitions

Developments of theoretical team effectiveness models created the need to define team coaching and specify team coaching approaches.

Team coaching definitions evolved over the time and addressed the emerging needs of effective teams. A brief summary of the prevalent team coaching definitions is presented in the table.

A Systemic Approach

Hawkins’ broad approach is called systemic, as it is not limited to the relationships between the team members but encompasses relationships that team members have with other stakeholders.

Systemic team coaching is defined as “a process by which a team coach works with a whole team, both when they are together and when they are apart, in order to help them improve both their collective performance and how they work together, and also how they develop their collective leadership to more effectively engage with all their key stakeholder groups to jointly transform the wider business”. (Hawkins, 2014, p. 16). Hawkins argues that all effective team leadership team coaching needs to be systemic to be successful

Kets de Vries (2014; KDVI, 2017) also advocates a systemic approach using diagnostic instruments intervening at 3 levels: Individual (how a leader functions and behaviours that need development), Team (structure for team development), and Organisational (guidance for strategic discussions that centre around corporate culture and align values and behaviours to business strategy). Read more about Kets de Vries model here

Kets de Vries’ (KDVI, 2017) argues that “this approach not only provides leaders with better self-knowledge, but this knowledge can also be used in their interface with other organisational actors in a way that allows them to shape, influence, and leverage organisational dynamics” (Ibid., #3).

The instruments provide a systematic approach to assessing leadership and organisational effectiveness, and highlight the wider context such as organisational culture and values (2). In his earlier working paper (2014) Kets de Vries underlined the role of culture in corporate transformation through group coaching intervention. Case studies provided illustrate the link between the individual, group and ‘a larger system’.

In my view, Kets de Vries’ (KDVI, 2017) approach strongly resonates with Hawkins’ approach in developing collective leadership by engaging stakeholder groups and thus, transforming the organisation.

Models of team coaching

Writing in concurrence with Hawkins (2014), Kets de Vries (2014) accentuates the power of team coaching in transforming organisations and achieving shared objectives. Individuals “become mutually invested in encouraging the new behaviors that each has identified and committed to, working together to achieve their goals. This “group contagion” is a powerful way to make change happen. It makes group-coaching intervention a highly effective method for aligning teams in the pursuit of shared objectives” (Kets de Vries, 2014, p. 12).

My personal interest in Kets de Vries’ strategic approach stems from my professional work with corporate strategies. His “High-Performance Group Coaching Intervention Process” is targeted at a top corporate level of executives and aims at transforming the group of executives into a ‘real team’. The process goes through the following key stages:

- Interviewing participants and undertaking assessments, looking for ‘mindfulness’ and motivation;

- Contracting individually and as a team

- Homework assignments and peer coaching

- Running coaching interventions with an additional facilitator/coach which is helpful in handling conflicts and blindspots

- Using specific activities like “self-portrait exercise” in the coaching event, processing Personality Audit and Leadership 360 feedback, achieving self-discovery.

Through this coaching intervention, “The group becomes a self-analyzing organization. Executives—now a real team—often demonstrate a remarkable level of emotional intelligence, given the quality of their interventions” (Kets de Vries, 2014, p. 17). It is evident that Kets de Vries applies more emotional intelligence instruments and transforms the team through a cathartic experience and awareness.

Research (Lawrence & Whyte, 2017) suggests that the dominant team coaching models used in Australia for structuring coaching programs are:

1) Hackman and Wageman (2005) model based on developmental approach. Motivational coaching is recommended for the first meeting, which is consistent with Kets de Vries’ search for motivation to change the organisation. A range of approaches are identified within a spectrum of directiveness and non-directiveness, from operational conditioning to process consultation (cited in Clutterbuck, p. 95).

2) Clutterbuck’s (2007) approach which is more connected to organisational learning and is consistent with Senge’s Learning Organisation (LO) concept. Clutterbuck explicitly delves into the aspects of a learning team, as learning helps organisations to become more effective. He analyses the 6 types of teams for learning (3) and proposes different coaching ways according to the type of the team.

3) Hawkins’ approach which, in my view, consolidates the view of a team as a learning system and the emotional work of the team (the latter is resonating with Kets de Vries work). Hawkin’s (2014) approach is explicitly systemic. He proposes a model of the Five Disciplines of High Performing Teams (p. 10). Each discipline represents a difference challenge for a team coach.

4) Thornton’s relational approach (2010, cited in Lawrence & Whyte, 2017).

My interest was to gain a more in-depth understanding of the HOW. I have chosen 2 models for further analysis: Hawkins (2014) and Lencioni (2012)

1) Hawkins (2014) proposes a set of questions to measure the progress in each of the 5 disciplines. Below is a summary of the key questions for each discipline:

2) Lencioni (2012) in Four Health Disciplines proposes that organisations need to be smart and healthy to be successful. The “smart” attributes are related to strategy, marketing, finance and technology. The “health” attributes are about minimal politics and confusion, high morale and low attrition.

In my view, this model reflects a systemic approach as it goes beyond the team boundaries and addresses the needs of a wider system, the organisation. The step-by-step process would provide a sufficient framework for a team coach to design a systemic coaching program using powerful questioning.

What does it take to be a Team Coach?

Although this subtopic is not directly relevant to my starting point of analysis, I was nevertheless keen to probe into the question ‘So what does it take to be a team coach vs a facilitator?’

Hawkins (2014) captured “the spiritual aspects of this craft” (p. 217) and developed a list of 13 capacities of a team coach, that included the capability to serve the larger system, a relational perspective (‘see the dance and not just the dancers’), ‘learning into the future’, and creative triangulated thinking. Hawkins’s core capacities reflect the essence of Senge’s Fifth Discipline (1990), the underpinnings of the Learning Organisation concept.

Clutterbuck’s (2007) approach is linked to learning teams and calls for the team coach’s capabilities related to facilitation of organisational learning. He argues that an external team coach may need to adapt a facilitation approach and urges to view the role of a Team Coach from three distinct perspectives which require different skills: work team leader, manager coach and external team coach. The coach’s influence ranges from the level of engagement with the task (Team Leader Coach) to providing feedback and motivating performance (Manager Coach). Notably, the External Team Coach is not required to understand the technical processes of the task but the need to bring a wider perspective, investigate cause and effect, and create insights. The focus of the Team Coach’s role is on reflective practice, learning conversations and making practical use of each other’s contribution to work tasks (ibid.).

I suppose both, Clutterbuck and Hawkins, were influenced by Senge’s organisational learning philosophy. As previously mentioned, both concepts, ‘team coaching’ and ‘team facilitation’ are embedded in it.

Conclusion

Writing this paper was a genuine learning experience for me providing an opportunity to reflect on my professional practice as well as draw on team coaching literature that was new to me. I felt I had to venture beyond a mere definition space in order to grasp the essence of concepts, and this expanded the scope of my topic.

My key take-away learning is that a Facilitator ‘moves’ the work processes while a Coach (often an external partner) enables development and core learning of individuals so that they become real teams maximizing their collective capabilities and transforming organisations.

Both coaches and facilitators may use cross-functional facilitation and coaching skills, however, the clarity of the role leads to greater team effectiveness.

Footnotes

(1) P. Senge ‘The Fifth Discipline’. According to Senge, The Learning Organisation is the one that facilitates learning and transforms itself.

(2) Two main instruments used, Personality Audit and 360 (Kets de Wries, 2014)

(3) The six types are Stable teams, “Hit” project teams, Development alliances, “Cabin crews”, Evolutionary teams and Virtual teams (Clutterbuck, 2007, p. 149-150).

Reference List

- Bimrose., J., Brown, A., Holocher-Ertl, T., Kieslinger, B., Kunzmann, C. , Prilla, M., Schmidt A. & Wolf C., (2014). The Role of Facilitation in Technology-enhanced Learning for Public Employment Services. International Journal of Advanced Corporate Learning, 7(3), 56-63.

- Carr, C. & Peters, J. (2013). The experience of team coaching: a dual case study. International Coaching Psychology Review, 8(1), 80-98.

- Clutterbuck, D. (2007). Coaching the Team at Work. Nicholas Brealey International, London.

- Eisele, P. (2013). Validation of the Team Diagnostic Survey and a Field Experiment to Examine the Effects of an Intervention to Increase Team Effectiveness. Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal, 12.

- Hackman, R. & Wageman, R. (2005). A Theory of Team Coaching. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 289-287.

- Hawkins, P. (2014). Leadership Team Coaching in Practice. Kogan Page, UK.

- IAF (2015). The International Association of Facilitators <https://www.iaf-world.org/site/ >viewed 18 November 2017.

- ICF (n.d.). <https://www.coachfederation.org/credential/landing.cfm?ItemNumber=2206> viewed 15 November 2017

- Kaner, S. (ed). (1996). Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision Making, 11th edn, New Society Publishers, Canada.

- Katzenbach, J.S. & Smith, D. K. (2005). The Discipline of Teams. Harvard Business Review, 83(7/8), 162-171.

- Kets de Vries, M.F.R. (2014). Vision Without Action is a Hallucination: Group Coaching and Strategy Implementation, INSEAD Working Papers Collection, 41(1-18).

- KDVI (2017). A Systemic Approach, “How does one go about diagnosing …”, Kets de Vries Institute, <https://www.kdvi.com/news/68-how-does-one-go-about-diagnosing-and-assessing-what-is-going-on-in-the-individual-team-or-organisation-and-what-the-real-issues-are >, viewed 17 November, 2017.

- Lawrence, P. & Whyte, A. (2017). What do experienced team coaches do? Current practice in Australia and New Zealand. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 15(1), 94-113.

- Lencioni, P. (2006). Team Dysfunction. Leadership Excellence, 23 (12), p.6.

- Lencioni, P. (2012). In smartness and in health. Training Journal (June), p. 12-16. Online edition available http://www.trainingjournal.com

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, Currency Doubieday, US.

Taurins © 2018